Published in 'Templar History Magazine', issue 12

Also in 'A Fourth Part of a Circle: The Journal of Freemasonry' Vol. 3,

#2 (USA/Canada ISSN:1499-8521) as 'Warren Uncovered: the Career ot

General Sir Charles Warren' (c) Gordon Napier

![]()

![]()

From the hunt for the Temple of Jerusalem to the hunt for Jack the Ripper

General Sir Charles Warren GCMG KCB FRS RE (1840-1927) looked the very model of a 'great Victorian'. He had a great Victorian moustache, and a uniform covered in great Victorian decorations. His career was as extraordinary as any from that eventful age, and although very much an establishment figure he remains somewhat enigmatic. Though his association with Jack the Ripper may tarnish his name, Warren was also a key figure in military and Masonic history, as well as an archaeological pioneer.

Freemasons share with the medieval Templars their identification with

the ancient Temple of Solomon. The Temple in Jerusalem occupied the plateau

of Mount Moriah, and housed the mysterious Ark of the Covenant. Later

the Ark vanished, and the Temple itself was destroyed, rebuilt and then,

in AD 70, mostly destroyed again. Eventually Islam took over the site,

holding it sacred due to legends that Mohammad ascended to consort with

God from the rock, which had formed the foundation of the Temple's altar.

Around this outcrop Muslims built the sublime Dome of the Rock. Through

subsequent centuries, they guarded the site against violation. After the

First Crusade, though, Jerusalem fell temporarily into Christian hands

and at length the first Knights Templar occupied parts of Temple Mount.

The Templars' declared agenda was the defence of pilgrims, but many believe

that the knights probed the site, searching for some ancient treasure,

perhaps buried scrolls, or even the Ark itself.

Arms of the United Grand Lodge of England

The Knights Templar were suppressed two centuries later. Some have said,

though, that Templar traditions were carried on by Freemasons. One such

tradition, according to this speculation, may be what Graham Hancock calls

a 'secret and never ending quest' for the Ark of the Covenant (which appears

as the crest above the heraldry of the United Grand Lodge of England).

James Bruce, the eighteenth-century Scot who explored Ethiopia seeking

the source of the Blue Nile, was a Freemason, and may have had an undeclared

agenda there in locating the Ark. The first westerner, meanwhile, to seriously

examine Jerusalem's Temple Mount in modern times was also a Mason, and

he may have had a similar ulterior motive.

Charles Warren, born in Bangor, Wales, joined the Royal Engineers as a

young Subaltern in 1857. He had attended Cheltenham College, the Royal

Military Academy at Sandhurst and finished his training at Woolwich. Freemasonry

was quite common among officers in the British armed forces. Warren was

initiated into 'the Craft' in Gibraltar, in 1859. Though also an evangelical

Christian, Freemasonry would remain an important part of his life. Progressing

through the grades of Freemasonry, he would have taken part in rites and

learned of the mythical founder of the Brotherhood, Hiram Abiff, architect

of Solomon's Temple 'who lost his life rather than betray the sacred trust

reposed in him'. Warren would have come to know the tale of Hiram's murder

by the three ruffians- apprentices named Jubelo, Jubela and Jubelum, (collectively

termed the Juwes). When Hiram refused to pass to them the secret knowledge

of Masonry, the jealous trio had slain him with their tools.

Warren was a scholar as well as a soldier. In 1867 (released from military duties), he led an archaeological expedition to Jerusalem, for the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund. The Fund had been active since 1865, and this was to be its first major project. Palestine was then part of the Ottoman Empire. Warren secured the Turks' permission to survey and excavate around the old city and Temple Mount. For a Freemason, initiated in a lodge symbolically representing Solomon's Temple, the opportunity to penetrate the site of the original must have seemed alluring. Living up to his name, Warren soon found himself uncovering a considerable network of unknown passages and chambers. It became clear that an underground labyrinth lay beneath Jerusalem. He apparently named one Second Temple period chamber as the 'Hall of the Freemasons.'

Hall of the Freemasons, Jerusalem, discovered by Warren c. 1868.

Real trouble arose when Warren's team began to clear a tunnel passing

north from the southern wall of the Temple compound, passing under the

caverns known as 'the Stables of Solomon' and towards the heart of the

plateau. The sound of the diggers disturbed the faithful at prayer in

the al-Aqsa mosque above, and soon a violent riot broke out, with the

Muslim worshippers assailing the workmen with stones and driving them

out. The Turkish governor, Izzet Pasha, ordered the dig to be called off.

Warren was thwarted, and failed in several subsequent attempts to re-enter

Temple Mount. Needless to say he never found the Ark. (Later, the eccentric

Montague Brownlow Parker, actively looking for the Ark in 1910, would

provoke even bloodier riots by sneaking into the Dome of the Rock at night

and trying to cut his way below the rock to a secret chamber where they

believed the Ark lay hidden. He and his team were likewise forced to abandon

their attempts).

Warren's survey work in Jerusalem was nonetheless of great value to archaeology.

He accurately reconstructed the plan of Herod's Temple. He located many

hidden vaults, drains, wells, aqueducts cisterns and secret passages.

His expedition discovered the underground water conduits, reaching across

the central valley to the spring of Gihone beyond the city walls (though

not the spring itself, which were located by the Parker expedition). All

this illuminated the topography of ancient Jerusalem. (Another objective

of the project was to improve the water supply of the modern city).

Another officer of Engineers on Warren's expedition, meanwhile, Charles

Wilson, recovered artefacts of possible Templar origin, some allegedly

from the controversial tunnel running under Temple Mount- suggesting that

Hugues de Payens and his brethren had indeed ventured there. The finds

include spurs, a spear tip, a sword hilt and a leaden cross. (These items

have passed to Robert Brydon, a Scottish 'Templar archivist' claiming

descent from Wilson). Warren returned home in 1870, due to ill health.

He held a command at Dover, and then at the school of gunnery at Shoeburyness

in Essex. He also found time to write on archaeology, publishing 'The

Recovery of Jerusalem' (1871), and later 'Underground Jerusalem' (1874)

and 'The Temple and the Tomb' (1880). Clearly this topic was an abiding

passion. His work fuelled public interest in the Bible lands, which made

possible the famous Survey of Western Palestine (an ambitious topographic

project carried out under Warren's military colleague Lord Kitchener).

Warren, meanwhile, in 1876, was posted to South Africa, as a special commissioner

of the Colonial Office. His surveying skills were called for in establishing

the exact boundary between the Orange Free State and Griqualand West.

Warren soon returned to active service. He commanded the Diamond Field

Horse in the 'Kaffir War' between 1877 and 78. An ongoing land conflict

had arisen between white Cape colonists (British and Boers), and the native

Bantu tribes to the northeast, (known disparagingly by the whites as 'Kaffirs'

or infidels). This formed a prelude to the Zulu War. Warren was severely

wounded in battle, and mentioned in dispatches three times for his bravery.

He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, before returning to England to

convalesce. He was appointed to the school of Military Engineering at

Chatham, in 1880, as chief instructor.

Two years later Warren went to Egypt, leading the search for the lost

expedition of Professor Edward Palmer (an orientalist who had ostensibly

gone there to procure camels, but who was actually engaged in espionage

for the secret service). Warren discovered that Palmer and his companions

had been murdered. It emerged that Palmer had been ambushed by Arabs,

taken to the Wadi Sudr and shot on the edge of a gully. Warren located

the remains of Palmer and two colleagues, Lieutenants Haynes and Burton

(both fellow Royal Engineers). He also brought their murderers to justice.

For this he was awarded a Knight Cross of the Order of St Michael and

St George, (KCMG- a knighthood for officials serving the crown in relation

to foreign affairs). In 1883 he was also made a Knight of Justice of the

Order of St John of Jerusalem.

Following an unsuccessful attempt to enter politics in England, Warren

was back in Africa, as part of the second military expedition to attempt

to relieve Khartoum, in the Sudan, where his doomed friend General 'Chinese'

Gordon was besieged. Afterwards he was sent south to Bechuanaland, where

he successfully restored order, earning the GCMG (Knight Grand Cross).

He set up the land commission, which finalised the borders, and played

a part in the founding of the town of Mafeking, on land given to the whites

by the local native chief. (Mafeking became the capital of South Africa's

North West Province, and was later made famous in the Boer War, for the

217 day siege, during which Badon Powell, another friend of Warren's,

led the British defence, and used boys as messenger 'scouts'.)Warren was

recalled to England, and in 1886 become the Commissioner of the Metropolitan

Police in London. The Metropolitan Police, founded in 1829, coverd all

of London but for the central 'Square Mile' (which was covered by the

City of London Police). The previous Commissioner, Sir Edward Henderson

had been sacked for failing to prevent protests against unemployment turning

into violent riots. Warren's appointment was welcomed by The Times which

reported that he was 'precisely the man who sensible Londoners would have

chosen to preside over the police of the Metropolis'. He was seen as a

moderate but strong leader, who could bring order out of chaos. He had

the support of Hugh Childers, Gladstone's home secretary. Unfortunately

for Warren, the Gladstone government soon fell, and was replaced by the

Conservative administration of Lord Salisbury. Salisbury replaced Childers

with Henry Matthews, a man with whom Warren found it increasingly difficult

to work. Warren began to lose popularity when, later in 1886, violent

incidents occurred, miring the Lord Mayors parade. Later Warren was accused

of mishandling things when a protest in Clerkenwell turned into a riot.

At about this time Warren was also finding time to continue his Masonic career. He was a key member of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge#2076, a lodge founded in 1884, dedicated to Masonic research. The Lodge had started to meet regularly in late 1885, when Warren had returned from Buchuanaland. He served as Founding Master. He also wrote an article for the Lodge On the Orientation of Temples. (Meanwhile in Jerusalem, Charles Wilson completed a second Ordinance Survey, publishing the results in 1886. He recorded the existence of a cave under the Dome of the Rock, and an ancient channel leading from it thought to have been dug to carry away the blood of sacrificial animals). Queen Victoria's Jubilee celebrations of 1887 passed off peacefully, but for when a constable wrongly charged a seamstress, named Miss Cass, with soliciting. Her employer sued the police. Warren behaved tactlessly, and managed to alienate both parties during the ensuing enquiry. Warren's approach to policing was summed up in his statement that London's safety and security depended on the 'efficiency of the uniformed police constable acting with the support of the citizen.' He favoured visible policing as a means of crime prevention, and believed that the police should be paragons of moral standards. He therefore came to quarrel with Monro, the head of CID and secret division, who favoured under-cover detective work and tackling criminals using whatever methods necessary. Warren's ideal soon proved to be unrealistic. Large-scale protests against unemployment and social injustice took place in Trafalgar Square throughout 1887. Warren repeatedly asked the Home Secretary for a ban on public gatherings. Things came to a head on Sunday 13 November, when some 40,000 protestors confronted 2,000 policemen. Violence erupted when Warren's men tried to clear the square. Warren, directing things personally, called for army reinforcements, including Grenadiers and mounted Lifeguards. Many were injured in clashes and allegedly one protestor died. The day came to be called 'Bloody Sunday.' The leader of the Dockers Union was arrested, while a radical MP named Cunninghame was among those injured in the fighting. Warren was vilified in the left-wing tabloid press after this, and had several subsequent riots to contend with. The events of the following year had the biggest impact on Warren's reputation.

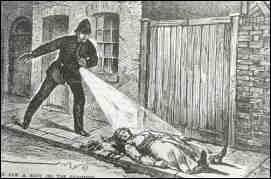

Discovery of the first victim.

The Whitechapel murderer first struck on 31 August 1888. The body of Mary Anne Nichols, 43, a prostitute, was found in Bucks Row, in the squalid East End district of Whitechapel. The woman's throat had been cut and her stomach mutilated. She was the first of the five accepted victims, all poor prostitutes. The next was Annie Chapman, 47, found in Hanbury Street, on 8 September. Her throat was cut, her stomach and genitals were severely mutilated, and some of her entrails had been drawn over her shoulder. Post mortem examination showed that her uterus had been taken. Next came Elizabeth Stride, 43, found in Berner Street on 30 September, with only her throat cut. The murderer had been disturbed before he could perform more mutilations. However, on the same night he also claimed the life of Catherine Eddowes, 46, cutting her throat and mutilating her face and stomach. Her body was photographed, sewn up after a post mortem, which had revealed that her uterus and left kidney had been taken.

Body of Catherine Eddowes, Whitechapel murder victim

Finally, on 9 November, Mary Jane Kelly, 25, was found in her unlocked room in Millers Court. According to the Assistant Chief Inspector, Melville McNaghten, Mary was 'said to have been possessed of considerable personal attractions'. Well, not when her killer had done with her. Her body and face had been subjected to an orgy of butchery. Her heart seemed to be missing.

These murders caused popular hysteria; especially after letters apparently from the mystery killer began arriving at newspaper offices and police stations. The first arrived on 27 September, at the Central News Office. It was written in red ink, and the murderer was taunting those hunting him. ůMy knife is so nice and sharp I want to get it to work right away if I get the chance. Good luck, Yours truly Jack the Ripper Don't mind me giving the trade name. Later, another letter accompanied a parcel containing a human kidney. London had a psychopath on its hands.

Warren's response to the Ripper murders was controversial for various reasons. Though he drafted more men into the area, including Detective Inspector Abbeline, little progress was made. It was as though they were hunting a phantom. Warren thought that bloodhounds might help track the Ripper. On October 11, he personally trialled two (Barnaby and Burgho) in Regents park. The trials were unsuccessful, for the dogs could not hold a scent through crowded areas. Some newspapers poured scorn on Warren's antics, even reporting that one of the dogs had bitten him, and Jack the Ripper wrote 'Dear Boss, I hear you have bloodhounds for me now.'

On the night of the double murder, a bloodstained part of Catherine Eddoewes' apron had been found in a doorway in nearby Goulston Street. Above it, PC Alfred Long discovered the chalked words:

The Juwes are

the men That

Will not

be Blamed

for nothing.

When Sir Charles Warren arrived on the scene, Superintendent Thomas Arnold asked for permission to wash away the writing. Arnold was in charge of keeping the peace in an area with a large Jewish community- predominantly refugees from pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe. He had a constable waiting with a wet sponge already. Warren, apparently appreciating that the graffiti could provoke an anti-Semitic riot if the Jews were linked to the murders, quickly agreed. The City of London Police, (on whose turf Eddowes' body had been found) and others criticized Warren's hasty erasure of a potential clue, before it could be photographed. It was, after all, too late to stop the writing on the wall becoming common knowledge. Warren himself soon issued a statement that the word Juwes did not mean Jews in any known language, (earning the personal thanks of the chief Rabbi).

As a Masonic historian, Warren would have known, though, that 'Juwes' was a collective term for the three murderers of Hiram, in Masonic teachings. Moreover, in the lore, the fugitive three, Jubelo, Jubela and Jubelum, lament their crime and imagine being punished for it in macabre ways which are slightly similar to the mutilations Jack the Ripper gave his victims (including the entrails being cast over the shoulder). It has also been noted that the mutilations on Catherine Eddowes's face included two inverted 'V' shapes, which could be construed as Masonic compasses. (The name of the place where the body was found, Mitre Square, has also been read by some as a masonic message). Some have gone so far as to call the mutilations 'Masonic retribution', though this is grasping at straws. Moreover the three 'Juwes' of the legend are the enemies of Masonry, so to read the graffiti as the veiled boast of a Masonic assassin makes little real sense.

Researcher Melvyn Fairclough, like Stephen Knight, has written that the Ripper murders were part of a grand Masonic conspiracy. (Mary Kelly had supposedly been the nanny of a child secretly born to Prince Albert Victor Edward. The Prince- heir to the throne and a Master Mason of the Royal Alpha Lodge- supposedly had a habit of 'slumming' and had allegedly married a Catholic commoner in secret. Mary Kelly had allegedly escaped the Masonic/police attempt to arrest all concerned. After slipping into prostitution she had told her four older associates, who had then attempted to blackmail the crown. The increasingly implausible theory has another prominent Freemason, William Gull- the royal physician- as the Ripper, acting with the coachman John Netley, and feeding poisoned grapes to the victims in his carriage. All this has been broadly discredited. There is no evidence that the Ripper's victims even knew each other, and if they knew a great secret why did they keep silent and wait to be picked off by the murderer? An unfortunate snag that spoils a good story!) The Masonic link to the Ripper crimes is altogether tenuous. However, if Warren was not a conspirator, and if he did not believe 'Juwes' to be a misspelling of 'Jews' then perhaps he thought the graffiti was part of an attempt to frame the Freemasons for the killings. Finally, though, there is little evidence either way. Though some at the scene thought the Goulston street writing looked new, it remains possible that it had nothing to do with the murder.

There was much pressure on Warren to catch the Ripper, who was humiliating the police. There was even speculation that if the murderer was not apprehended then it might bring down the Government. A crowded public meeting after the Mitre Square murder called for the resignations of both Warren and Matthews. The penny newspapers wereout to destroy Warren, still blaming him for the Trafalgar Square violence, and accusing him of various blunders. They criticised his refusal to offer a reward for information that might lead to the Ripper's arrest (Warren had indeed been opposed to offering a reward, but had then changed his mind, only to have the scheme vetoed by the Home Office). The Ripper timed his last murder so that Mary Kelly's remains would be found on the morning of the Lord Mayor's show, and cast a grim shadow over the festivities. That was also the day that Warren tended his resignation as Commissioner. Not everyone was glad of it. Sir Robert Anderson, (who had succeeded Monro as head of CID), had found, against all expectation that Warren had been 'perfectly frank and open' in his dealings. 'When his [Warren's] imperious temper could no longer brook the nagging Home Office ways of the period, I felt sincere regret at his going.'

After leaving the police force, Warren picked up his military career, commanding troops in Singapore, and then served back in England. Meanwhile in 1889 the resentments of the Dutch-speaking Boers against British expansionism in South Africa (and the incursion of British gold-prospectors into the Transvaal and Orange Free State) brought about the Second Boer War. Warren took part, as a Lieutenant General, commanding the 5th Division, South African Field Force. He joined up with General Redvers Buller, the overall commander, in Natal, and in December 1899 found himself commanding an assault on a hill called Spion Kop. The Boers proved unexpectedly tough fighters, and the battle went disastrously for the British. The British managed to take the hill, but were unable to dig trenches into the rocky ground and were exposed to bombardment from other Boer positions. One wonders if the spectacle of butchery reminded Warren of what he had seen in the streets of Whitechapel. After a day of hell the order came to withdraw.

British troops in the Boer War

Warren took a share of the blame for the heavy casualties of Spion Kop. Historians of the conflict have accused him of incompetence, though officers of the time were more critical of Buller. Later, Warren had opportunity to redeem himself somewhat. He was involved in the offensive that relieved Natal. He succeeded in making a forced crossing of the river Tugela, and gained a victory at Pieters Hill that opened up the way for the relief of Ladysmith (which Buller saved at the cost of more British casualties than the total force opposing). British fortunes in the war would improve as Lord Roberts and Kitchener assumed control. After Britain secured victory in 1902, Warren served as an administrator in Cape Colony. He reached the rank of General, finally retiring in 1905. He devoted the remainder of his life to work with Scouts and other youth movements. He also published memoirs from his time in South Africa, and continued his Masonic research. He died at Weston-super-Mare in January 1927, leaving two sons and a daughter to mourn him, his wife having predeceased him.

Sources

Paul Begg. Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History (2003)

Paul Begg, Martin Fido and Keith Skinner. The Jack the Ripper A-Z (1996)

Melvyn Fairclough. The Ripper and the Royals (1991).

Graham Hancock. The Sign and the Seal (1992)

Karen Rallis. The Templars and the Grail (2003)

Various. The British Empire (Journals)

Online Sources

http://www.bibleplaces.com/warrenshaft.htm http://www.pef.org.uk/Pages/Warren.htm http://www.met.police.uk/history/ripper.htm http://www.casebook.org/police_officials/po-waren.html http://www.freemasonry.bcy.ca/aqc/ http://www.royalengineers.ca/WilsonC.html http://www.templemount.org/warren1.html http://redcoat.future.easyspace.com/egypt.htm http://www.btinternet.com/~willie.meikle/iss5n1.html http://www.pinetreeweb.com/conan-doyle-chapter-15.htm