This article was first published in 'Templar History Magazine' issue 10, which also featured interesting contributions from other writers. Pleas see www.templarhistory.com for back-issues.

A grief stricken Mary Magdalene came to the tomb of Christ three days

after the Crucifixion. According to John's gospel, she found the stone

removed from the tomb's entrance, and rushed to fetch the disciples Peter

and John.

So they ran both together: and that other disciple did outrun Peter,

and came first to the sepulcher.

And he stooping down and looking in, saw the linen cloth lying, yet went

he not in.

Then cometh Simon Peter following him, and went into the sepulchre, and

seeth the linen cloth lie,

And the napkin, that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes,

but wrapped together in a place by itself.

Then went in that other disciple… and he saw and believed.

John, 20, 4 to 8.

The relic has been housed in the Catheral of St John the Baptist in Turin, Italy, since 1578. It has long been venerated as the burial shroud of Christ. It appears to be imprinted (as though miraculously) with his image, bearing the marks of torture and crucifixion. To many the shroud is a disturbing and fascinating object, with an air of mystery that captures the imagination. But could the shroud have genuinely supernatural origins? Could some charge of divine energy have burnt this image onto the material, at the moment of Christ's Resurrection? Did the disciples find this relic in the empty tomb, and pass it down to be held in reverence through the ages? In 1988, with the Church's permission, a small sample of the Turin Shroud was removed for scientific tests. It came as a blow to some when the results of the radiocarbon dating placed the shroud between AD 1260 and 1390.

The Turin Shroud

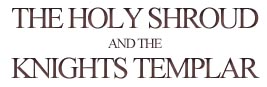

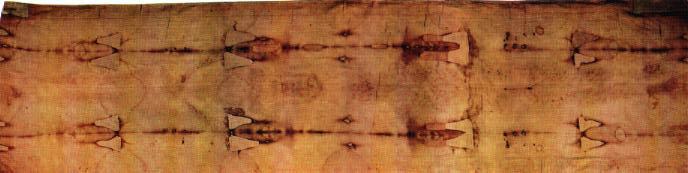

The white linen shroud measures 14 ft 6 inches by 3 ft 7 inches. It bears the image of a man, 6ft tall and well built, with long hair and a short beard. The faint image is a yellowish brown in colour. It shows the full length of the man's body; front and back, as if the long, narrow cloth had been folded over his head. Since the carbon dating, various theorists have tried to account for how an object with such markings could have been created in the Middle Ages.

The shroud came to light in the mid 14th century, when Geoffrey de Charney, a French noble, had it exhibited in Lirey. Doubts about the relic's authenticity are nothing new. In 1389 the Bishop of Troyes denounced the shroud as a fake, which he alleged was painted in about 1355. The shroud, however, does not seem to be a painting in the traditional sense. There are no brush-marks, and no pigments are in evidence. Neither are there any medieval artistic stylisations. The shroud survived into the modern age, and was first photographed in 1898. When the photographer, Seconda Pia, developed the pictures, a revelation resulted. The photographic negative showed the shroud with a perfect, three-dimensional positive image. The shroud itself is therefore a perfect negative. No medieval artist, arguably, could or would have painted a picture that way.

The South African Art Historian Dr Nicholas Allen suggested that the shroud itself is in fact an early form of photograph; made by soaking the sheet in silver sulphate solution to make the fabric light sensitive. Of necessity, a body would have been suspended before the sheet (twice in order to get both views) to achieve this, with lenses positioned between. This set up would have needed to be left for several days, while the surface reacted with ultra-violet rays. This seems hardly a satisfactory explanation for the shroud, though. There are no other examples of medieval photography, and it seems highly questionable whether anyone would have crucified a man and hung his body up somewhere merely to fake a relic. Moreover, the man in the shroud does not seem to be hanging. The shroud seems to have covered a real body, that of someone who had suffered gruesome injuries, identical to those suffered by Jesus.

Christopher Knight and Robert Lomas in their book 'The Hiram Key' propound the notion that the Knights Templar were both the heirs to the ancient Essene sect and the forerunners of the Freemasons. They wrote that the Templars revived an Essene ritual involving symbolic resurrection of the dead, and incorporated it into their secret initiation rites. Props used in the ceremony included a shroud, skull and bones. Guillaume de Paris, the Grand Inquisitor, swooped on the Paris Temple in 1307, to arrest the Templars there (his master, King Philip IV, having decided to suppress the Templars on charges of unholy worship). Knight and Lomas speculated that the Inquisitor and his men found the shroud the Templars used in the rite, in a Templar shrine filled 'with anti-Christian ornamentation: pyramids with eyes at their centre, a star studded roof and the square and compass…' Concluding that Jacques de Molay, must be a terrible heretic indeed, the Inquisitor tortured the Grand Master there and then in his own dungeons. The Inquisitor had his men crucify de Molay, and thus secured the Grand Master's confession, then he wrapped de Molay in the shroud. This was the real, forgotten origin of the Turin Shroud, or so Knight and Lomas argued.

The only evidence in favour of this theory is that the shroud emerged in 1357 in the possession of a noble called Geoffrey de Charney. Another, earlier Geoffrey de Charney had been the Templar Preceptor of Normandy. (He was arrested alongside de Molay in 1307, and like him confessed to heresy. In 1314, when De Molay publicly retracted his confession, Geoffrey de Charney showed solidarity; and was burned with him at the stake by a vengeful King Philip IV on an island on the Seine). Knight and Lomas find supporting evidence for their theory in a carving of the crucifixion at Rosslyn Chapel, Lothian, Scotland. This carving has the perpetrators wearing medieval garb, supposedly revealing the scene to be the crucifixion of De Molay, remembered in the Templar tradition. They also produce a picture of de Molay that bears a resemblance to the face in the Turin Shroud.

There are several flaws with this version of events. For a start, no such unchristian decorations were found in the Paris Temple. If they had, then they would have been brought as evidence at the tribunals that the Templars faced following their arrests. There was no shroud and no skull and crossed bones (though there was a female skull in a silver reliquary, said to be that of a virgin martyr). There is no evidence of Templars using shrouds in their rituals. Most importantly there is no evidence that Jacques de Molay was ever crucified. He may have suffered some maltreatment before he first confessed, but if he had been crucified it would surely have provoked widespread outrage. If he had born the stigmata when he later appeared in public, then some of those who witnessed would surely have noted this. When he made his final declaration of Templar innocence of heresy, he said that those who confessed had done so through fear of torture. If he (or any other Templar) had been crucified, then de Molay would surely have included this detail in his last defiant speech.

There is some doubt whether the Geoffrey de Charney who was in possession of the Shroud in 1357, was a relative of the Preceptor of Normandy, his namesake, who died in 1314. It is unlikely, meanwhile, that the Grand Master would have been released to the Templar Geoffrey de Charney's kin to recover from this form of torture, as the Hiram Key's authors supposed. Both de Molay and de Charney almost certainly remained in Royal custody throughout. As for the Rosslyn Chapel crucifixion carving; during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance it was customary for depictions of Biblical events to be given contemporary settings. The picture of de Molay that Knight and Lomas reproduced, meanwhile, seems from its style to have been drawn centuries after the Grand Master's death. Therefore, the crucified man who left his impression on the Turin Shroud was probably not Jacques de Molay.

The Crusaders were zealously devoted to a large fragment of the 'True Cross', which they found in Jerusalem, and lost at the battle of Hattin in 1185. Other supposed relics from the Passion of Christ were important to Medieval Catholics too. The Veil of Veronica, for example, was a relic reputedly marked with the face of Jesus, after she wiped his face with it on the path to Golgotha. There was a contender for the Holy Lance of Longinus (that pierced Jesus' side) at Constantinople, while another Holy Lance was unearthed by the knights of the First Crusade at Antioch. Louis IX of France, meanwhile, would own two different contenders for the Crown of Thorns (the second one was bought from a cash-strapped Latin Emperor of Constantinople- Byzantium having fallen to French Crusaders and Venetians in 1204). There were various places boasting Holy Nails, too. That some relics were faked seems obvious. Surely it is doubtful, though, whether anyone would have gone so far as to crucify a man simply in order to fake a shroud. (Especially considering the fact that the Bible actually makes no mention of any markings on the Shroud of Christ, so any old shroud could have passed for it!)

After the mid 14th century, the history of the Turin Shroud is well recorded. It emerged in 1357, and it was taken to Chambéry some time after 1453. In 1578 it was taken to its present home. At various times it has been shown publicly, during religious festivals, inspiring a frenzy of adoration from pilgrims. In 1610 it was exhibited in Turin and Vercelli, to mark the Beatification of Carlo Borromeo. It visited Torrione castle where Giovannni Battista Della Rovere depicted it in fresco, held by Duke Almedo IX of Savoy, and the Blessed Carlo Borromeo, with the Black Virgin of Opora between them. (The same artist painted a 'Descent from the Cross' showing Christ being enshrouded.)

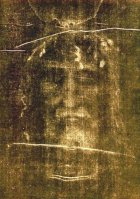

There is in fact some evidence that the relic existed before the 1350s. There is a small manuscript in Budapest (known as the Pray Codex), dating to the 1190s. A crude illustration shows Christ being taken down from the cross and placed in a shroud. The dead Chris is shown naked with arms crossed at the wrists and thumbs hidden, just as the figure in the shroud is. (This pose of the suffering Christ was replicated in Byzantine iconography of a type known as the Man of Sorrows). Below the buial scene is a depiction of the 'three Maries' encountering the angel and finding the shroud in the empty tomb. The shroud in the illustration features a distinctive detail: a group of four small round holes in an 'L' formation. The same group of holes may be seen in the Turin Shroud (and also on a drawing of the shroud in Liege, Belgium, dating to 1516, predating the fire that burned additional holes into the fabric). If the illustrator of the early Hungarian document saw the shroud, then the carbon date result for the shroud must be wrong. (Conversely, if the carbon dating is correct, then the forger of the shroud must have seen the illustration, or perhaps an image it was based on).

It has been said that if the shroud was faked between 1260 and 1390, then the forger must have been some genius; able to produce handiwork that withstands space age forensic scrutiny. Scientific tests in 1978 concluded that the image on the shroud was probably made by contact with a body. They also identified a stain of human blood on the fabric. Other scientists found the shroud to contain limestone dust seemingly from Palestine and pollens possibly from that region and also from Turkey. Recent examination of the shroud, prior to it's being hermetically sealed in a special container, revealed a tiny seam in the weave of the linen. This feature was similar to a seam found in a cloth excavated from Masada, a mountain fortress in the Holy Land that fell to the Romans in AD70 effectively marking the end of the Jewish Revolt. Apparently no such stitching has been found in the medieval era. Another notable feature is the fact that the wounds from nails of crucifixion, evident in the shroud image, pierce the man's wrists and ankles rather than his palms and feet. Some believe this better reflects the crucifixion method practiced by the Romans.

These findings tend to suggest that the shroud was not forged for Geoffrey de Charney, in the 1530s. Therefore, how his family came by the object is a mystery. In 1453, the Duke of Savoy obtained the relic. His heirs moved it to a chapel in Chambéry in Southern France. Whilst there, the shroud was damaged in a fire in 1532, and was lucky to survive. The silver plate on the reliquary in which it was stored began to melt, and molten silver dripped through the folded shroud leaving rough, triangular holes with blackened edges. Faint water stains on the shroud do not correspond with these, though, so clearly had nothing to do with extinguishing the fire. It seems from the positions of the water marks that, in an earlier period, the shroud was folded up a different way, and possibly stored in a tall clay jar (similar to those in which the Dead Sea Scrolls were found), which collected water at the base. It is tempting to interpret this as additional evidence of a first-century origin for the relic.

The sample of the shroud analysed in 1988 was cut from one of the corners. Even if it was an original part of the fabric, this area would have been that at greatest risk of contamination through handling. The sample does not match the rest of the shroud, moreover, being darker and coarser in consistency, suggesting the possibility that it was part of a later patch or mend. Perhaps the most compelling support for an earlier date for the Shroud of Turin, though, comes from a less famous relic in a Cathedral in Northern Spain.

Oviedo Cathedral houses a wooden chest covered in silver, called the Ark of Relics. It contains the Sudarium Domini. The Sudaruim is a humble, bloodstained rag. It is held to be the napkin cloth that was wrapped around Christ's head after his body was taken from the cross and before it was entombed. Unlike the Turin Shroud, the Sudarium has a very ancient documented history. Early Christians took it from Jerusalem, for safety in AD644, to escape the invading Persians, under Chosreos II. They took it to Alexandria, and then to Spain. It was moved north from Toledo, in 718, to Oviedo, ahead of the Muslim advance. The ancient wooden ark was given silver plating with Romanesque ornamentation. Astonishingly, tests on the blood on the Sudarium have revealed it to be of the same rare AB type as the blood found on the Turin Shroud.

The Sudarium of Oviedo

Investigators have also postulated that the patterns of blood on the Sudarium correspond to wounds evident on the figure in the shroud. If each of these relics is genuine, then their survival seems almost miraculous. However, accepting the Turin Shroud as the burial shroud of Christ does not necessitate belief in miracles. The markings it bears could have had perfectly natural causes. The presence of acid or bacteria in cloth, just as in paper, causes discolouration over time, as it reacts with the air. The controversial recent film, 'The Passion of the Christ' does not grossly exaggerate the condition Jesus would have been in before his death. He would have been plastered in blood and sweat, which could have accelerated bacterial growth on his skin. As he lay enshrouded and entombed, the micro organisms could have adhered to the cloth, where it touched the body. Later, exposure to air would have caused those contaminated areas of cloth to discolour quicker than surrounding parts. Acids from certain bodily secretions could have similarly resulted in those areas going brown with time. The discolourations might therefore have appeared gradually, perhaps some time after the shroud was washed, and the appearance of the image of Jesus would have appeared miraculous. This may explain why the gospels do not record there being an image on the shroud when it was found in the empty tomb. Some of the embalming spices mentioned in the biblical account (John 19:40) may also have contributed to the darkening of the cloth. The only thing about the Shroud of Turin that contradicts the Biblical narrative (and one of the oddest things about it) is the fact that it appears to have been folded over a body rather than wound around one. This, however, may be explained by mistranslation.

The pollen found in the Sudarium confirms its documented wanderings, through Egypt and Spain. The pollens identified in the Turin Shroud hint at a different story. The shroud left the Holy Land and was in Turkey. Some identify it with a Byzantine relic, much famed in past times, called the Mandylion. This seems doubtful, however, for the Mandylion cloth was supposedly marked only with the face of Christ- it was supposedly the Veil of St Veronica. It was recorded as being in Edessa in the 500s AD. The face in the shroud does resemble various copies of the lost Mandylion, though, leading to the intriguing possibility that the Mandylion, too, could have been an authentic relic of the Passion. The Mandylion was taken to Constantinople in 944, and probably looted from there after 1204, when the French knights of the Fourth Crusade sacked the city. They and the Venetians looted much treasure, including religious relics. According to a letter written by Theodore Ducas Angelos to Pope Innocent III in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, the loot included 'most sacred of all the linen in which our Lord Jesus Christ was wrapped after his death and before his resurrection' Theodore hinted that the Shroud had been taken to Athens. The Templars were not recorded as being militarily active in the Fourth Crusade. Many regarded as scandalous when the Crusaders diverted towards Byzantium. The Pope himself was originally furious. As Helen Nicholson has discovered, there was at least one Templar in the retinue of the Crusade's leader and later 'Latin Emperor of Constantinople' Baldwin of Flanders. This Templar, Brother Barozzi, acted as a messenger between Baldwin and the Pope. He was charged at one stage with delivering gifts including plundered relics to the Pope, no doubt to mollify Innocent's anger and to buy his approbation of the Occupation (which in the short term had achieved the subjugation of the Eastern Church to Rome, even if its long term consequences were the weakening of Byzantium which facilitated the Ottoman conquests of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries) Barozzi also received gifts on behalf of the Templars- indicating if nothing else that the Templars were not averse to the idea of laying their hands on formerly Byzantine relics and treasures. These did not include the Shroud, in this instance and at any rate Barozzi was robbed of these treasures by Genoese merchants.

Some speculate that the Mandylion fell into the Templars hands, and inspired the rumours that they worshipped an idol in the form of a head. The head painted on a board, found half a century ago in Templecombe in the South West of England (where there was a Templar Preceptory) bears a resemblance to the Mandylion, and indeed to the head of the shroud. The Templars and Hospitallers both associated themselves with the Holy Sepulchre, and both acted as escorts to the 'True Cross' when it was carried abroad. Both also escorted a vial of Christ's Blood from the Holy Land to England in the 1250s, so clearly both took an interest in relics of the Passion.

There is no record of the Knights Templar possessing the shroud. If they had possessed it, it is curious that they did not advertise it in order to draw pilgrims

Still, theirs was a clandestine brotherhood, and it cannot be ruled out that they were secretly the guardians of the shroud. Not everyone was so ready to exploit the Holy Relics they possessed. Some relics were indeed guarded tacitly. The Templars may have obtained the shroud from Athens. If the story of it being there is not true, though, then it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the Templars found the shroud during their sojourn in Jerusalem. Others propose that they inherited it from the heretical Cathars, who may have inherited it from Gnostic Christians in the near east. There were stories of the last Cathars smuggling a great treasure away from their stronghold at Montsegur in 1244, before embracing martyrdom at the hands of their Catholic persecutors. Certainly the shroud found its way to France by some means if it was not created there.

There are those who think that the Shroud of Turin should be tested again,

to see if it could be of first century date after all and to discover

more of its secrets. Perhaps, though, it ought now to be left alone. In

some cases a mystery is more valuable than facts and figures, and the

shroud in question may be one such case.

Addendum

The Templars' secrecy rendered them vulnerable to accusations of heresy. The order was suppressedin the 1300s and the brethren subjected to what became the largest and most scandalous trial in history. Confession were secured, often through torture by Inquisitors and royal agents, and were recorded by clerical notaries. The confessions described depraved induction rituals and the worship of various idols. Vatican researcher Barbara Frale has recently discovered another confession that stands apart and seems to support the idea that the Templars possessed the Holy Shroud itself. The deposition was that a French Templar named Arnaut Sabbat, describing his initiation, which had taken place in 1287:

"(I was) shown a long piece of linen on which was impressed the figure of a man and told to worship it, kissing the feet three times," said the document. "

( Telegraph, 6 April 2009 see http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/italy/5113711/Knights-Templar-worshipped-the-Turin-Shroud.html )